Muslims Missing from Native American Heritage Month

Native American Heritage Month is observed in November as “a time to celebrate the traditions, languages and stories of Native American, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and affiliated Island communities and ensure their rich histories and contributions continue to thrive with each passing generation.”

The Native American Muslim is often missing from the usual narrative of remembrance and celebration. Their inclusion is an important and necessary factor of past and present history.

Mahir Abdal Razzaq is a Cherokee Muslim. He shares his perspective on a message board about Native American Muslims about a not-so-visible history of the Cherokee people, one that speaks of the presence of Al Islam amongst the native people:

“My name is Mahir Abdal Razzaaq El, and I am a Cherokee Blackfoot American Indian who is Muslim. I am known as Eagle Sun Walker. For the most part, not many people are aware of the Native American contact with Islam that began over one thousand years ago by some of the early Muslim travelers who visited us. Some of these Muslim travelers ended up living among[st] our people.”

Abdal Razzaq continues, “For most Muslims and non-Muslims of today, this type of information is unknown and has never been mentioned in any of the history books.”

“There are many documents, treaties, legislation and resolutions that were passed between the 1600s and 1800s showing that Muslims were in fact here and were very active in the communities in which they lived.”

“Treaties such as Peace and Friendship that [were] signed on the Delaware River in the year 1787, bear the signatures of Abdel-Khak and Muhammad Ibn Abdullah. This treaty details our continued right to exist as a community in the areas of commerce, maritime shipping, and [the] current form of government at that time, which was in accordance with Islam… All of the documents are presently in the National Archives as well as the Library of Congress,” Abdal Razzaq further points out.

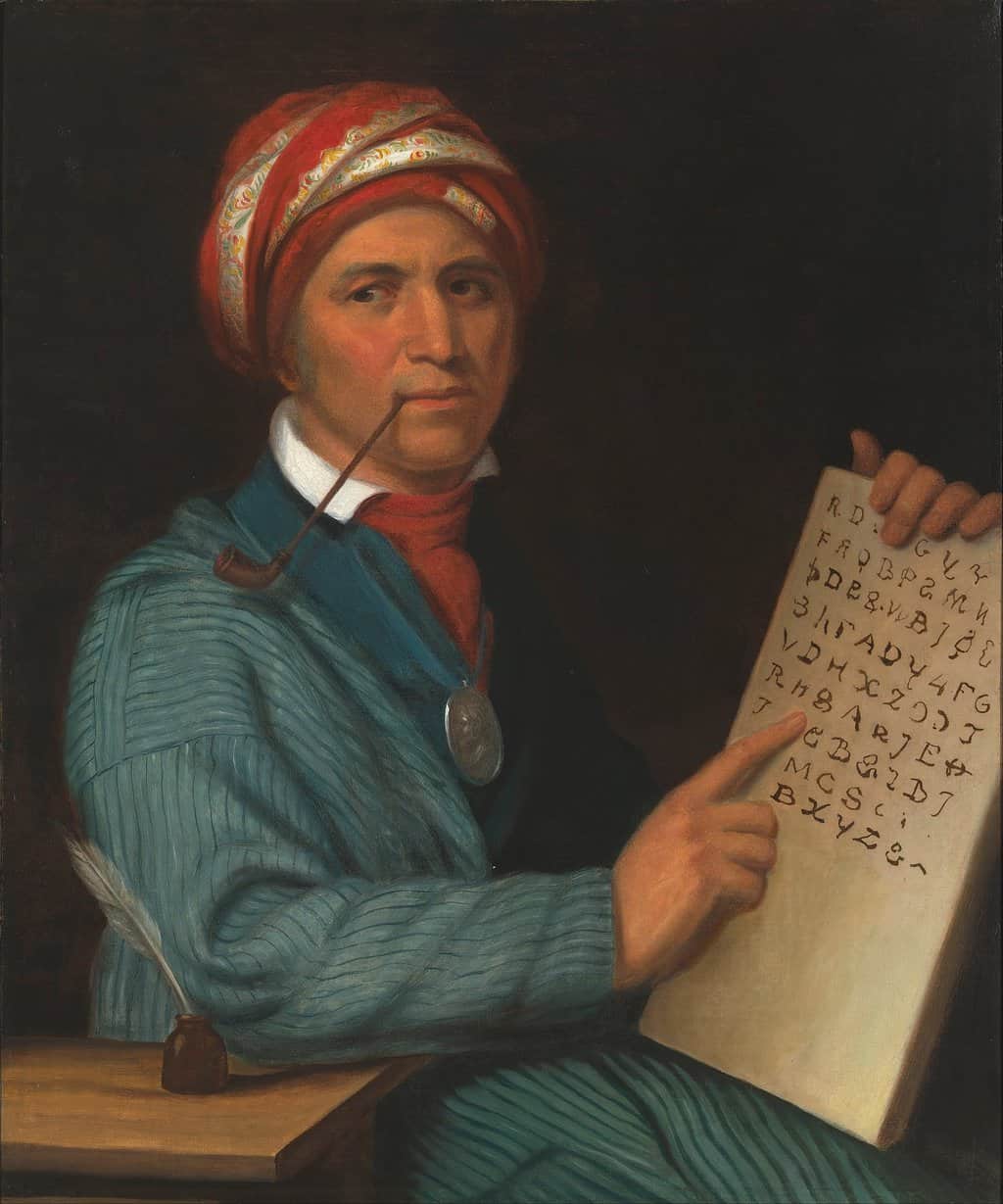

He goes on to share, “Almost all of the tribe’s vocabulary include[s] the word Allah. The traditional dress code for Indian women includes the kimah [khimar] and long dresses. For men, standard fare is turbans and long tops that come down to the knees.”

“If you were to look at any of the old books on Cherokee clothing up until the time of 1832, you will see the men wearing turbans and the women wearing long head coverings. The last Cherokee chief who had a Muslim name was Ramadhan Ibn Wati… in 1866,” Abdal Razzaq concludes.

NDN Collective, summarizes the historical impact of the Indian Removal Act and how it negatively affected the native peoples of this country:

“In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act as a means of claiming and expanding the [U.S.] territory by violently removing Native Peoples from our homelands to territories not our own. This act was designed to cut relationships Native peoples had with the land by removing us, destroying our homes, our medicines, our crops, our livestock, and killing any who resisted.”

This is only one example of many in a phenomenon of the time coined as manifest destiny.

According to an article on the subject by ushistory.org: “At the heart of manifest destiny was the pervasive belief in American cultural and racial superiority. Native Americans had long been perceived as inferior, and efforts to ‘civilize’ them had been widespread.”

In another example, worldhistory.org states: “The Pequots [tribe] were forbidden to call themselves by their name or inhabit their ancestral lands… War resulted in the near extermination of the Pequot tribe and opened up the regions of Connecticut and Long Island to further English colonization, allowing for easier westward expansion afterwards.”

Verbal accounts passed down amongst Pequot families through history have been one way to keep their people’s history alive.

Maryam Abdul Karim born in New London, Connecticut, gives us her verbal account of her life as a Native American Muslim and a member of the Pequot Tribal Nation.

“As a member of the Pequot Tribal Nation, that had been recognized by the Federal government only to have that recognition appealed by the state of Connecticut, there certainly resonates a feeling of resentment about the failure to give First Americans their just due.”

Abdul Karim’s personal narrative depicts the struggles of people of the past that tie in with the struggles of indigenous people today.

“As a descendent of African slaves on my father’s side, and Pequots on my mother’s side, there is a double jeopardy for many of us in the form of compounded historical oppression, leading so many of us naturally to Islam as our saving grace.”

Abdul Karim’s narrative continues: “My personal story of coming into the fold of Islam, occurred during my years of attending graduate school in New York [when I came] into a community of predominantly… American Muslims [of African descent] in 1970. This was a very comfortable adaptation for me.”

Indigenous Americans of different tribes have also found commonality in the Islamic religion.

The Consortium for Educational Resources on Islamic Studies (CERIS) shares a project produced by The University of Pittsburgh, Native American and Indigenous Muslim Stories (NAIMS): Reclaiming the Narrative.

“Reclaiming the Narrative project, is the first-ever photo narrative project to center the… experiences of Native American and Indigenous Muslims in the United States. This research amplifies Indigenous Muslim voices to highlight the challenges, strengths, and needs of this small but incredibly diverse community.”

CERIS gives these statistics:

“Native Americans are often invisible in our public discussion of America, and even more so in any discussion of Muslims in the United States. As a group, Native Americans broadly makeup 1.8% of the US general population. As such, they are often overlooked, invisible and underrepresented in public conversations and decision-making.”

CERIS continues, “Muslims broadly make up an estimated 1.1% of the US general population. Among Muslims in the United States, Native Americans make up just 1-2%. There is an absence of awareness and lack of representation of Native American and Indigenous Muslims both in the broader US public and within the US Muslim community.”

Basheer Louis Wapata a Lakota Muslim from South Dakota gives his personal narrative and shares some historical and present day information about his people in an interview.

“I am a Lakota. When someone doesn’t understand that, I say I am a Sioux Indian… When Columbus came over to the Western hemisphere, he thought that he had landed in India, so he started calling the people Indians… We try to educate people about who we are and the language that we speak, and that most of us prefer not being called Indians.”

Basheer expounds on information about his people.“ South Dakota is where the majority of the Lakota Sioux oyate (nation) live. The Lakota word “oyate” is like the word “ummah” in Arabic. We have about seven or eight tribes in South Dakota, one in Nebraska, one or two in Minnesota, three in North Dakota, and one in Montana. There are a lot of us. Out of all the tribes in America, we are the third largest behind the Navaho.”

Basheer shares his story of his conversion to Islam. “I converted to Islam on September 21, 2001. I did some studies about the religion for several months… Islam connected me to my Creator.

“I wanted to have a direct connection with God, our Creator, rather [than] go through a preacher or someone else… I started to think that there should be no need for an intercessor, a third party. After learning about tawheed, I felt like this was exactly what I was looking for,” he further explains.

Basheer speaks on a point of reflection on tawheed before embracing Islam. “In Lakota, we say “tunkasirra,” which is like tawheed… I hesitated for a few minutes before taking my shahada, thinking about all that Muslims were going through after the events of 9/11. But, after I thought about it for a few minutes, I thought to myself that Native Americans have been going through that and more since 1492.”

Basheer goes on to talk about how his people were persecuted, forced to forget their culture and beliefs, and how Christianity was imposed upon them: “Lakota and other Native people were, for the most part, historically, forced to become Christians. Boarding schools for Native Americans were a sad part of Indigenous and American history,… my ancestors told us stories about these schools”.

“Native American children were forcibly removed from their families, tribes, and homes and sent to schools like the Carlyle Indian School in [Pennsylvania] where they suffered all kinds of …abuse. The children were punished if they were caught speaking their tribal language, using their tribal names, or practicing their traditional religion,” he continues.

Considering the past struggles of indigenous Americans for centuries and all they still suffer today, Basheer shows his bravery and perseverance and gives examples of this. “I am equipped to deal with discrimination against Muslims as a Lakota Native American Muslim.”

These stories bring to light the struggle of the past and personal realities of today. One month to “celebrate” a forgotten oppressed indigenous people might never be justified or substantial.

Adeelah Ahmad